The existence of sand dunes depends on two things. One is the fact that dry sand gets blown about when the wind is getting up towards or above gale force.

This isn't always as simple as we might think. For example, where the sand is being blown from, anything can act as a mini-shelter from the wind, and the weight of a stone, for example, has some effect, holding the sand in place. So one outcome is that each pebble tends to finish up on the top of a little tower !

A lot of the sand is inevitably blown out to sea where it just sinks to the bottom.

The ways of blown sand can be mysterious indeed. If the wind is blowing along the beach the sand may accumulate in bands or stripes, a bit like embryo desert sand dunes perhaps.

Whether or not they develop depends on the strength, duration, and direction of the winds.

There can even be some unexpected elements of structure, with layering and corrugations.

However, wherever sand gets blown towards the existing dunes a building process can take place.

But it isn't very often the case that such a smooth, even layer of sand accumulates. It's more usual for accumulations to occur in odd corners, or wherever the swirling wind drops the sand.

So it's time to meet the vital partner in the dune-building process - the marram grass. This amazing plant is coarse and strong enough to withstand everything that the gales, sand-blasting, drought and salt spray can throw at it.

Sand movements are perhaps most obvious when, and where, a dry on-shore gale blows for hours at a time. The marram grass is undeterred by scouring and partial burial.

When disaster strikes in the form of gale-blown high tides the sand gets washed away. But the creeping stems and deep roots of the marram grass can survive.

However, there can be much more serious erosional events. The winter of 2009-10 witnessed what was evidently a fairly extreme example of wind strength and direction at times of high water springs causing major sand movements. Some places on Seahouses South (Annstead) beach were left with eight-foot high sand cliffs. It was only the earlier generations of marram roots and rhizomes (underground creeping stems) that prevented total collapse.

Mixed fortunes followed in later months, with short-term replacement of sand in some places, and further collapse in others.

But a broader view of that stretch shows features of long, level banking: it seems that major erosion and major rebuilding take place from time to time, maintaining the general alignment of the beach over time - fortunately.

The winter of 2012-13 was again fairly drastic at times, perhaps exaggerating the erosive phase on dunes immediately south of the Annstead burn. The chunky nature of the sand falls, held together with tough marram vegetation, again helps to ensure rapid recovery, hopefully before blow-outs cause too much further loss. On the other hand, drying out may result in mini-avalanches of sand.

In nearly every case some of the extremely tough underground stems of the marram grass survive, so that if and when a later wind refreshes those parts with in-blowing sand the plant is already there to start again with a fresh crop of new shoots.

But it isn't only the sea that can remove sand: a change of wind direction can do that too, especially so far as the youngest dunes are concerned, along the front edge so to speak. If the new wind has access to dry sand it results in a 'blow-out'.

Any undercutting of previously stable vegetation leads inevitably to collapse.

So the whole dune system is subject to constant change, to building and destruction, accretion and erosion. This is most obvious, perhaps, where there is a definite edge, as here along the Annstead Burn near the top end of the south beach.

Under normal conditions the pluses and minuses balance out. So although the very local shapes may alter with time, the total pattern and extent of the dunes change only very slowly. It now remains to be seen what effects climate change and sea-level rise may have.

As well as being able to spread through the sand by means of its roots and underground stems marram grass also has the more universal ability to flower and produce seed for yet wider spread. Flowering reaches a maximum in mid-August, as here on the Braidcarr beach south of the harbour.

But meanwhile, once any dune area has gained some permanent stability other kinds of plants can not only become established, they actually oust the marram grass. It's almost as if the marram needs instability and adventure !

So grassy areas develop.

But that's not like your nice fertile lawn at home. If there's not enough plant food available in this poor sandy 'soil' it's only mosses that can survive, perhaps with even tougher lichens.

Eventually shrubs are likely to make an appearance, from seeds brought in by birds.

A word of caution. Seahouses citizens take such an interest in their dunes that some folk are tempted to add flourishes which Nature might not have chosen unaided !

But with increasing stability and improving fertility other parts of a more permanent ecosystem arrive. They are nearly all invisible - microscopic or living underground. But the evidence is there in the form of molehills, for example.

There are some larger inhabitants, but they're rather shy, or come out only at night.

But there is a certain amount of evidence around, though ! - evidence of increasing soil fertility.

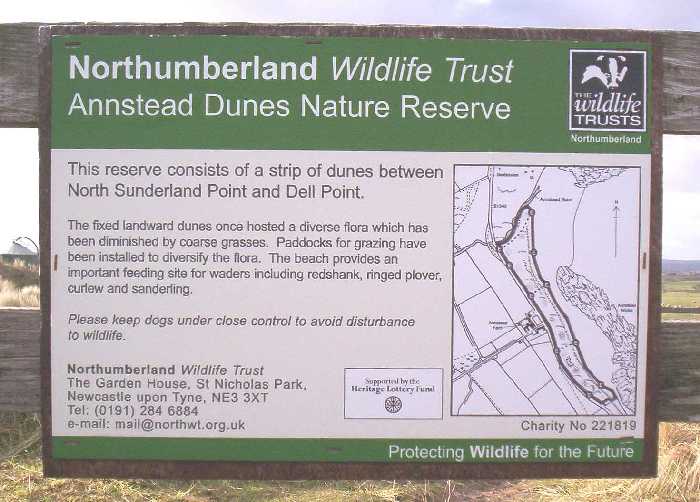

Sand dunes are vulnerable bits of our countryside. Trusts 'manage' them for us. They call on allies to help them, principally to prevent woody shrubs and trees getting the upper hand.

So the fences are there to control the livestock, not to keep us out !

|

HOME page

Location

Routes

Street plan

Attractions

Visit

Photo album

Walks to/from Sands Dunes Rocks Tidal Zonation Community Directory Trades Directory |